This is an original short story about a crisis of faith and a remarkable (and true) hand of God moment. Father Jack finished saying Friday morning mass at St. Rita’s, one of the two remaining Catholic churches for which he serves as duel pastor in this dying steel mill town in Western Pennsylvania. The usual four parishioners attend; people he calls his “faithful four” who keep him from talking to an echo chamber of empty pews. While they are regular morning mass attenders, they never sit near one another. They spread out on both sides of the main aisle, sometimes ten pews apart. Jack often wonders if they do this because they want to pretend the church isn’t empty or if they just want to be left alone with their sins and their prayers.

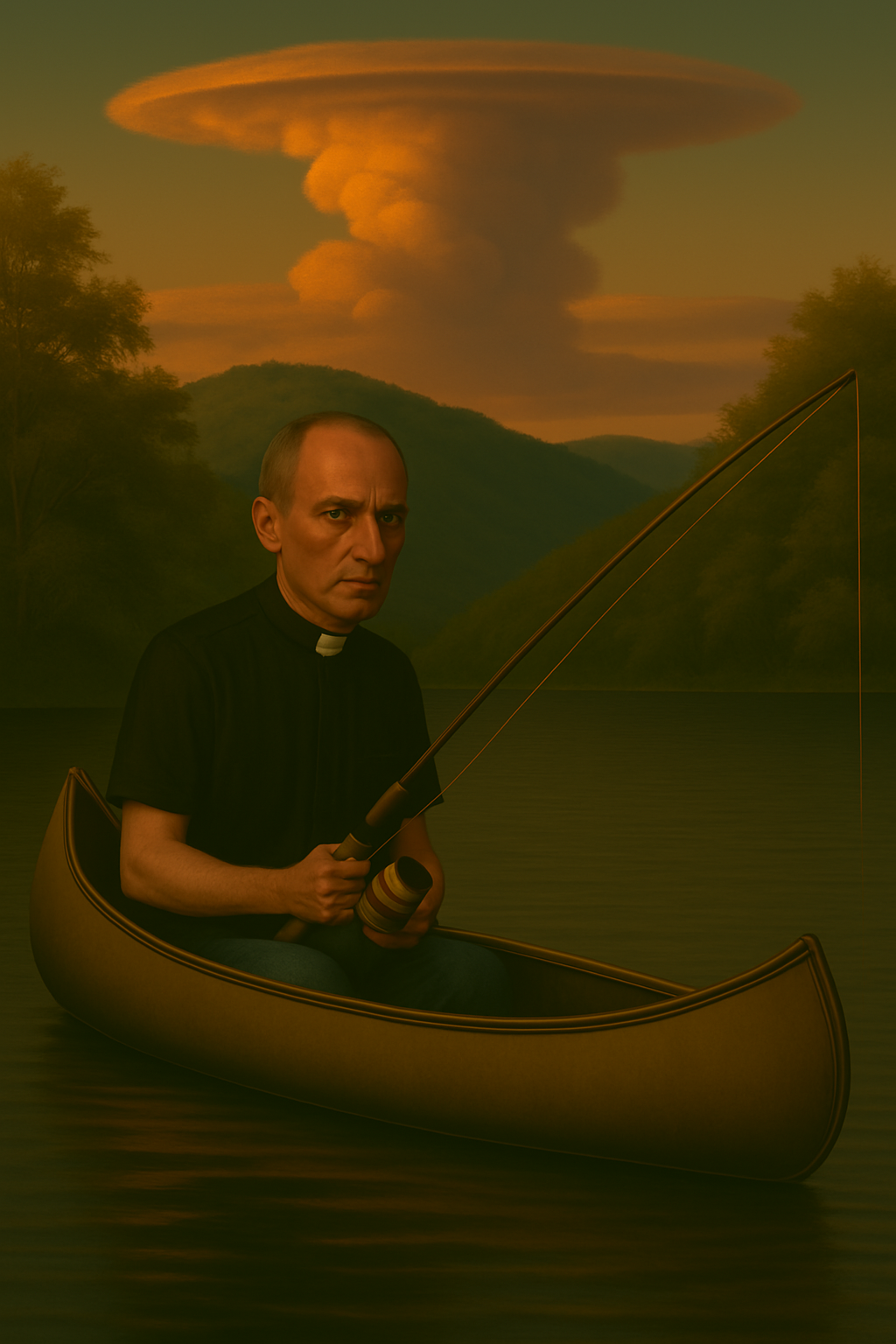

Since priests are required to say mass every day – regardless of attendance - Jack is neither deterred nor inspired by this now mundane ritual, performed in front of his four parishioners whom he sees as partners in denial of the future of this dying community. George - one of the “faithful four” - was an assistant manager at the local hardware store where he worked for 18 years before the store closed. After Friday mass, he assigns himself the job of making sure everything is prepared for the weekend worship. Burnt lightbulbs are replaced, kneelers are all turned upright and hymn books are neatly placed in the wooden racks at the back of each pew, ready for the hundreds of parishioners who will never come again. The Church was built in the 1930s and by the 1960s three masses were needed on Sunday, and each of them was standing room only. The last mass was especially packed. Late comers - mostly men and teenage boys - lined up out the front door that was propped open so the tardy but faithful could strain enough to hear the mass and fulfill their Sunday duty. Tommy – as he likes to be called even in his 78 years of age – volunteers to ensure the votives at the side alters have plenty of fresh candles. Tommy empties out the votive cash box near the right side alter. His finger joints so swollen and stiff with arthritis he can’t reach in and just pick up the coins. He has to pull the collection box full out of the votive cash drawer, using only his thumb and index finger like a clamp, and dump the coins in his opposite hand. “ $1.50 in change” he thinks “things are sure going to hell.” As Jack walks down the side aisle heading for his tour in the confessional, he stops to talk to Tommy. He and Tommy used to be fishing pals, but Tommy had to stop when the arthritis in his hands got so bad he couldn’t thread a fly on the end of the line. “Wish you could come fishing with me today, Tommy.” Jack said. This was the honest truth. Jack could be fishing for an hour with not even a nibble, and Tommy would wade over and recommend a different fly at a new spot, and by magic Jack would hook a brown trout. “I’m going to canoe out on Eagle Creek. What do you recommend?” Jack asked. “Hmmm…” Tommy paused, running his crooked fingers through his neatly trimmed gray hair “Late May… maybe try a Parachute Adams or a Quill Gordon fly.” “Thanks Tommy, I’ll give em a try” Jack answered as he walked to the confessional; dreading this part of his job. Jack settles into the middle seat of the confessional, puts on his purple stole, and flips on the discrete red light signaling that he is ready to hear the sins of his parishioners. On most Friday’s, the two widows of the “faithful four” confess their human frailties to Jack, who couldn’t care less. “What a waste of everyone’s time” Jack thinks. “I don’t need to hear how Doris gossiped about her sister-in-law or how Angela had mean thoughts about her neighbor.” To the outside world, Jack is a dutiful priest who says mass every day, who always has a smile or a kind word for his congregants, and who knows what to say to comfort grieving relatives. But Jack knows he is coasting. Jack regularly considers leaving the church, but at 60 years old, the former pastor of a dying church wouldn’t have many prospects in this fading community, he assumes. Jack spends most nights sitting in a high back chair in the parish house study, puffing on a Dutch Master cigar and drinking McCallan Scotch Whisky. Some nights he reads, mostly mystery novels or historical fiction books that make it on the New York Times reading list. Occasionally, he reads the bible – but he finds that increasingly less helpful. On Thursday night - after a bit too much Scotch – Jack’s thoughts turn to his future and down the rabbit hole of what he calls his faltering faith list. “How can I remain a priest when there’s so much Catholic shit I can’t swallow.” “I don’t accept the Church position on abortion. I’ve seen too many pedophile priests bounce from parish to parish with little concern for the families. The church espouses a preferential option for the poor but when push comes to shove, the bishop always comes down to a preferential option for church coffers. I don’t believe in hell, I’m not sure about an afterlife, and it’s been a very long time since I felt any real presence of God in my life.” At the end of the litany Jack hears himself say out loud, “Jesus God, what am I doing here?” Maybe this is a prayer for help, or maybe just a manifestation of exasperation. Jack isn’t sure, but it somehow makes him feel better to speak the hidden feelings of his wavering soul out into the universe. On Friday after mass and confessions are done, Jack heads to the mountains. He sits in the anchored canoe and lets the gentle current of the river sway him into a meditative state. “Things don’t get much better than this” he thinks. “fishing on the river. The smell of the Mountain Laurel. The crisp cool mountain air. It gives a man perspective.” Jack reels in his lure – a Quill Gordon that Tommy suggested - and casts it out again, trying to land it quietly upstream of a pool where he suspects a brown trout might be waiting for a fly to float by as a tempting snack; a trick he learned from Tommy. As Jack watches the lure meander its way downstream, his thoughts return to his ongoing internal debate. “The church won’t let me retire until I’m 75. I can’t do this for another 15 years.” “I love working with people, but I can’t keep faking that I believe in what the church is teaching any more. “ “I’m done. I’m a good administrator and I’m good with people. I’ll find a job, even if I have to become a salesman, or move out of town.” Jack was so deep into his own thoughts that he didn’t notice the wind pick up or the anvil cloud forming high in the sky and off to the north above the mountain behind him. He never heard the lightning that hit his canoe as the actual bolt arrived before the thunderous sound of it. He didn’t smell the ozone in the air and he likely didn’t initially feel the sterling silver cross and chain that he wears around his neck sear its shadow forever into his skin. Jack woke up in a flight for life helicopter as he was being whisked away to Allegheny General Hospital Trauma Center. He survived because people on shore saw what happened and acted. Two men called 911, and then used a powerboat to quickly get to Jack who was only 20 yards off shore. A retired nurse performed CPR on him, and it only took 20 minutes for the flight for life helicopter to arrive on scene. The fact that Jack survived the lightning strike isn’t surprising, as the vast majority of people struck by lightning do live, but their lives are profoundly changed. Many have mental and physical complications that they endure for the rest of their life. But a fortunate few exhibit heightened sensitivities or new and unusual abilities. It appears that Jack was one of those lucky ones. Doris was the first to have Father Jack hear her confession upon his return from rehab after the accident. After the perfunctory “bless me father for I have sinned” Doris launches into a screed about her sister-in-law, Gina. “ I know I’m supposed to love her and forgive her, but she’s tarnishing my husband’s name. And my name. She’s a widow just like me but she goes out to dances and bars and has men friends over.” “Doris” Father Jack said softly but firmly, as he interrupts her. “Are you angry at Gina or are you angry that your husband died too soon?” Jack asked. There is a long pause. “You never asked me that before” Doris exclaimed. “Well, I am asking it now, Doris.” Jack responds as kindly as he can through the opaque confessional barrier. “ Are you angry that your husband died too soon?” Doris began to cry as she told Father Jack about the vacations that were never taken, and quiet conversations over coffee that are long gone, and the tender moments they spent dancing. “Can you forgive your husband, Doris?” Father Jack asked. Doris’s tears are steadily falling now, dampening her folded hands as she kneels in the confessional facing Father Jack behind the screen separating sinner from confessor. “Yes. Yes, I think I can.” Doris professes. “I just miss him so much.” “You still love him, Doris. Embrace that” Father Jack implores. Doris never cried in the confessional before. But she also never felt so light and free afterward, as she did today. Before today, confession for Doris was just one of those things she did on Friday mornings after mass; the same as she has since Catholic grade school. She would recount her sins, Father Jack would give her a token penance of prayers to recite and she would be done and on with her day without giving it another thought. Today was different. Father Jack was different. It was like he could explain her pain and heartache in a deeper way than she ever imagined she could do on her own. By the time Father Jack retired, St. Rita’s was the only Catholic church remaining in town. Ironically it was Jack’s bout with lightening that helped the parish to survive. At first, people trickled in to Sunday mass to see firsthand the priest who was touched by God with a cross permanently scorched into his flesh. He could tell the ones who came to gawk. They would shake his hand after mass and stare at the space below his Roman collar instead of into his eyes, as if they were trying to imagine the burnt cross on his chest. But then, several began coming back. They found Father Jack to be humble and kind. He didn’t lecture about hell and damnation. He preached about tolerance and forgiveness, and about how God loves us even if we feel we don’t deserve to be loved. If someone wanted to talk, Father Jack always found the time. And he listened. He deeply listened not only to the words people spoke, but especially to the words, and fears, and desires left unspoken. It was as if he could somehow see in them. See through them. Jack took up fishing again after retirement, but only in streams where he can wade in and cast his line. No more aluminum canoes for him. Today, Jack is fishing one of his favorite sections of the Youghiogheny river that winds its way north through the Allegheny mountains. He has his bib high waders on as he stands in the cold and swift flowing river. With the shoreline behind him blanketed by overhanging trees, Jack fishes in the shade. The water is so clear that he stands patiently, knees bent bracing against the current, watching for a trout that he can entice with a fly and a well-placed cast. “This is more sporting.” Jack muses “I like stalking a particular fish, not just aimlessly casting about.” Jack touches the place on his chest where the burnt cross is still visible, knowing that he was swimming in a stream of doubt until he was stalked by God. Author’s Note: This is based on a true story of a priest in Wisconsin in the mid-1980s who was sitting in an aluminum canoe fishing and was struck by lightning. He was rescued by a Flight for Life program. He had a cross and chain scorched into his skin from the lightning strike. He survived.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMike Soika has been a community activist for more than 30 years working on issues of social and economic justice. His work for justice is anchored by his spiritual formation first as a Catholic and now as a Quaker. Pre 2018 Archives

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed